My first software project reached 24 million users

The online gaming website I built at 16 and sold at 19

IO games were blowing up in 2016 — Agar.io, Slither.io, Diep.io — simple browser games with addictive mechanics that anyone could play instantly. But there was no central place to find them all. I was 16, had just started teaching myself to code from YouTube and freeCodeCamp, and figured I'd build one.

The first version was embarrassingly primitive. Every game was a static HTML file that I'd copy, edit by hand in Notepad++, and drag over FTP to a $10/month VPS. No database, no templates, no framework — I barely knew what those things were. But the site worked, and that was enough.

I started promoting it aggressively on Reddit, learning through trial and error which titles got clicks and which got downvoted into oblivion. I got weirdly good at Reddit marketing — understanding the unwritten rules of each subreddit, the best times to post, how to write headlines and comments that didn't feel like spam. I was also teaching myself SEO on the side, obsessively optimizing every page, reading outdated blog posts about meta descriptions and header tags at 2 AM.

Then one day I was sitting in class, phone hidden under my desk, refreshing Google Analytics like I did every period. I noticed a traffic spike that didn't come from Reddit. My heart started pounding. I clicked through to the referral sources: Google organic search. I opened an incognito window and typed "IO games" into Google.

My site was ranking on the first page.

Within a week, it hit #1. And it stayed there.

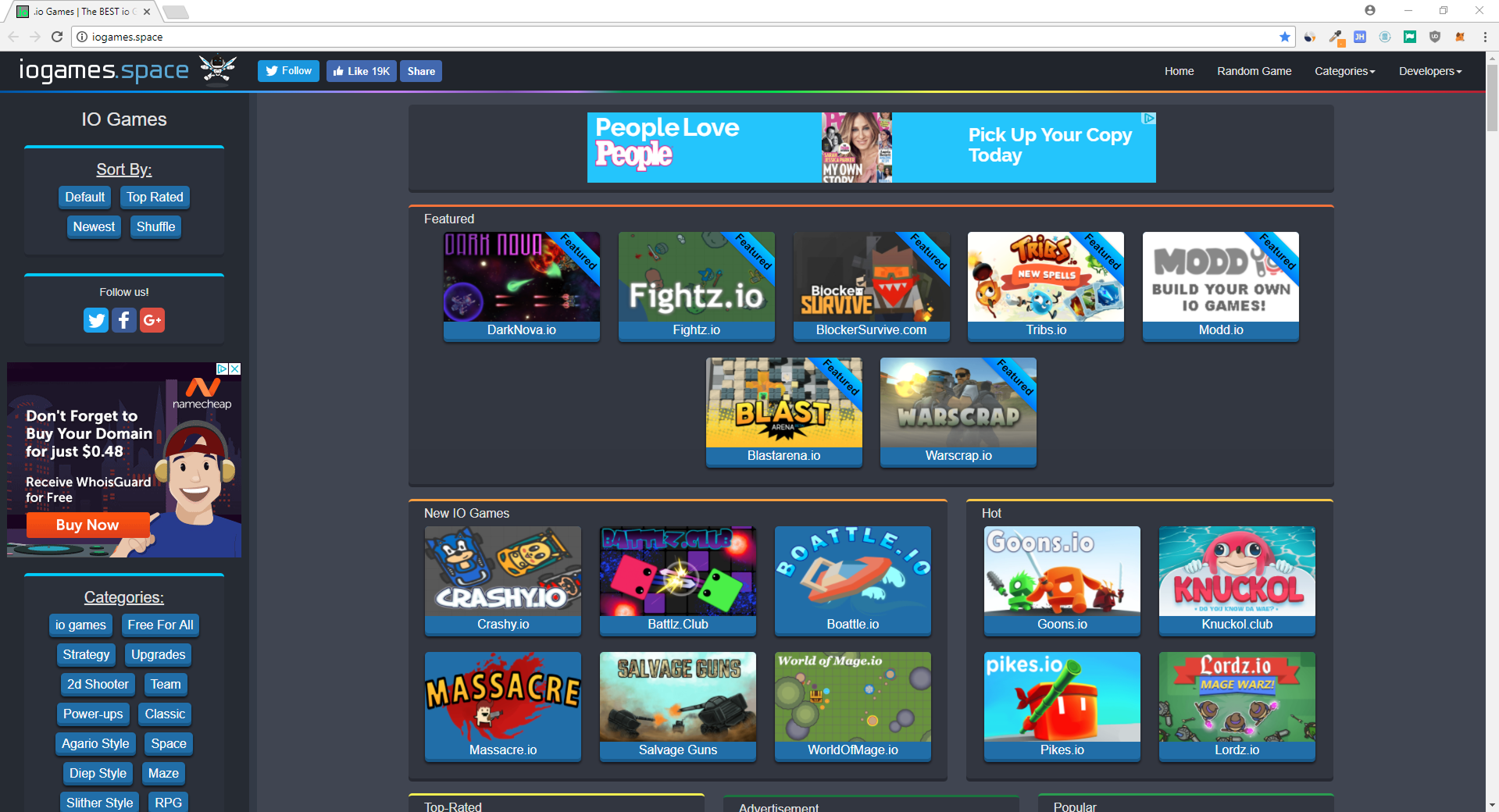

As the IO games genre went viral throughout 2016 and 2017, my site went with it. It became the flagship platform of the entire ecosystem — the place developers wanted their games featured, the place players went first. I don't think people were even consistently calling them "IO games" before my site helped popularize the term. The traffic graphs looked like hockey sticks. Hundreds of concurrent users became thousands.

That's when everything started breaking.

The shared hosting plan couldn't handle the load. Pages took 10+ seconds to render. The server would go down multiple times a day, and I'd get angry emails from Bluehost telling me I was violating their terms of service with my traffic levels. I was manually editing 50+ HTML files every time I wanted to change the header navigation. Adding a new game meant copying an existing file, find-and-replacing all the text, and hoping I didn't miss anything. I'd broken the site twice by accidentally deleting the wrong file over FTP.

I realized I had no idea what I was doing, and I needed to learn fast.

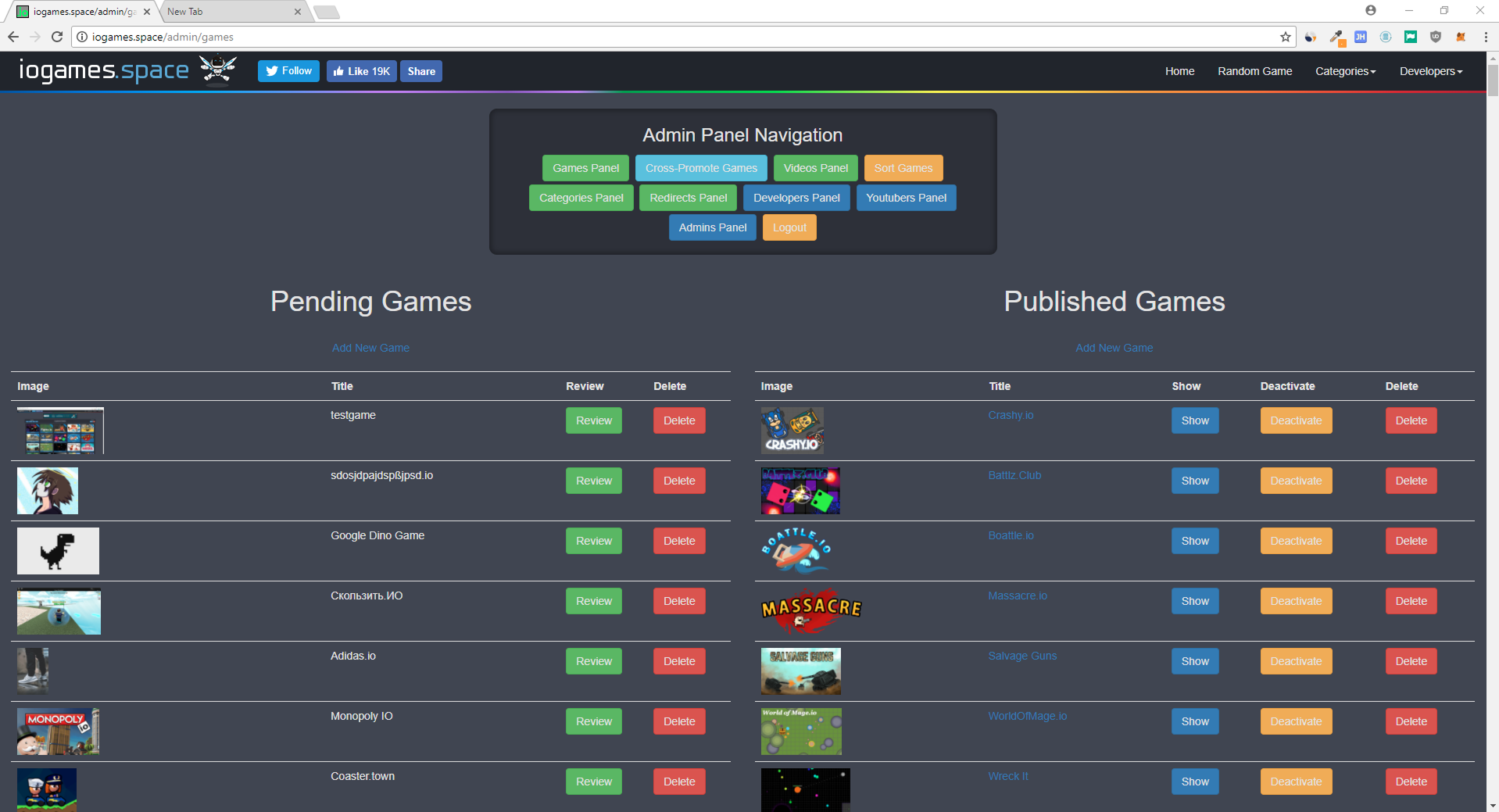

I spent two weeks going through every Ruby on Rails tutorial I could find, building and rebuilding todo apps and blog engines until the patterns started to click. Then I rebuilt iogames.space from scratch. I migrated to a VPS, set up a PostgreSQL database, and replaced those static HTML files with an actual application — dynamic templates, user authentication, an admin panel where I could add games in 30 seconds instead of 30 minutes. I built a developer portal where game creators could register, submit their games, and manage their own listings without me touching anything.

The homepage was the most important part. I knew that where a game appeared on the site directly affected its traffic — featured games got 10x the clicks of games buried lower down. With 200+ developers now depending on me for distribution, I felt a responsibility to make sure the system was fair. I built an algorithm that rotated games across different sections — featured, new, top-rated, trending — while making sure no game appeared twice on the same page. It took me three days of scribbling logic on notebook paper during class and another week of debugging before it worked smoothly. When the off-the-shelf analytics library started choking on millions of daily hits, I wrote a custom hit tracking server that could handle the load. Images went through S3 with Cloudflare CDN and automatic compression to keep load times fast.

I also built a Chrome extension that hooked into the platform's API, letting players browse and launch games right from their browser toolbar to improve direct traffic & retention. It quickly picked up over 50,000 installs.

I built the whole thing on Cloud9, a browser-based IDE, because it was the only way I could code at school. Every free period, every lunch break, I'd head to the media center, log into a public computer, and work on the platform. The librarians knew me by name. Then I'd go home and code until 1 or 2 AM. On weekends, I'd code for 12-hour stretches, often forgetting to eat.

The part I didn't expect was the ecosystem that grew around it.

Developers started building games specifically to launch on iogames.space because that's where the players were — guaranteed distribution to hundreds of thousands of people on day one. I set up a deal: link back to the platform from your game's main menu, and you get free promotion to the entire audience. Over 200 game developers signed up.

Some of them turned those launches into life-changing success.

Zombs.io was a viral sensation — within days it was getting hundreds of thousands of plays, within weeks it hit millions. The game was simple but addictive: build a base, gather resources, survive zombie waves. Players couldn't stop playing it. Moomoo.io followed a similar trajectory, leveraging the platform's distribution to reach a massive audience right out of the gate. Mope.io was another — a predator-prey game where you'd start as a small animal and eat your way up the food chain, leveling up into bigger and more powerful creatures. That one exploded too.

These weren't just traffic spikes. These were independent developers, many of them teenagers or in their early twenties, building games in their bedrooms and suddenly generating serious revenue — ads, in-game purchases, sponsorship deals. Their success created a virtuous cycle: great games kept players coming back to the site, which attracted more game developers, which brought more innovative games, which attracted even more players. It was a flywheel, and I was watching it spin faster every week.

Developers would email me their revenue numbers, thanking me for the traffic. I was 17, still living with my parents, and I'd built a critical distribution machine that hundreds of independent game developers depended on.

At peak, the site had over 2 million monthly active users and had reached 24 million unique players total.

I got invited to gaming conferences in San Francisco and LA. I met lots of interesting founders, some of whom became friends I still talk to today. Checking into hotels was a little awkward — I was 18, and most hotels had 21+ age restrictions. I'd have to wait in the lobby while one of my friends went to the front desk and pretended to be my dad, vouching for me so I could get a room key.

The acquisition offers started coming in during my senior year of high school.

First was Curse, a gaming media company that ran wikis and forums for major games. They flew me to their headquarters in Huntsville, Alabama and paid for my accommodations. I was 18, sitting in a conference room with their executive team, trying to act like I belonged there.

When Curse made their offer, it was life-changing money, which made turning it down an emotionally challenging thing to do.

But I'd done my homework. I spent weeks researching comparable acquisitions, probing the market for alternative interests, and triangulating the multiples that gaming platforms traded at. I built spreadsheets modeling my traffic growth, revenue projections, the value of my developer relationships and the goodwill I'd created. I tried to strip out my own emotional attachment and look at the numbers coldly: monthly active users, engagement rates, the competitive moat of being ranked #1 for "IO games" on Google.

Every model I ran said the same thing: my platform was worth significantly more than what Curse was offering. The IO games trend was still accelerating. My traffic was growing month over month. I had 200+ developers who depended on my platform for distribution, and several of them were generating six figures in revenue. The data was clear.

After Curse, other companies came knocking. Miniclip (one of the top online gaming websites at the time) reached out. So did a few other gaming networks and media companies who'd seen the traction and wanted a piece of it. But each offer was underwhelming — better than nothing, but nowhere close to what the spreadsheets told me the platform was actually worth.

The hardest part wasn't the first no. It was the second, the third, and so on. Every offer was real money. Life-changing money. Money that would have solved lots of problems. But I'd done the work. I knew my numbers. I knew what I'd built.

So I waited. I kept running the site, kept growing the traffic, kept building relationships with developers. And when the right opportunity finally came, I didn't have to think about it. I recognized it immediately.

The actual sale happened when I was 19. The former owner of AddictingGames.com reached out. His name was Bill, and he was re-entering the gaming space after selling his previous company. He wanted to build a new gaming network, and iogames.space was a prime target — the #1 IO games website in the world.

The negotiations went surprisingly smoothly. Bill was decisive and knew exactly what he wanted. I did too. We had a deal signed within a week.

I'd built this thing from nothing, and it had become part of my identity. Letting it go felt like giving away a piece of myself. But I was exhausted. Running a site with millions of users while taking a full course load meant I was constantly putting out fires — server issues at 3 AM, developer disputes, DMCA takedowns, ad network problems. I wanted to build new things, and I couldn't do that while holding onto this one. It was time to graduate to the next phase of my life.

A few DocuSign's later and it was done.

The wire hit my bank account three days later. I was sitting in my room when I got the notification on my phone. I refreshed my banking app a bunch times to make sure it was real. I sat there staring at my phone for probably ten minutes, not quite believing it.

Iogames.space became the foundation for everything I've built since. It gave me the freedom to take risks, to start companies without worrying about rent, to spend years working on projects that didn't make money right away. To level up my engineering skills and explore my curiosities unbounded by financial constraint. It changed the entire trajectory of my life.

But more than the money, what I think about most is the impact I was able to create with just a laptop and an internet connection. A simple, static HTML site I cobbled together in my bedroom — something I built because I was bored and wanted to learn to code — touched the lives of 24 million people from all across the world. Kids in Brazil, teenagers in Indonesia, college students in Germany, all playing games and sharing fun experiences with their friends on a platform I'd built, mostly during lunch breaks, skipped classes, and late nights.

I was 16 when I started and I had no clue what I was doing. I just knew I wanted to build something useful.

Turns out, that was enough.